Commercial Pain Points: Feature Creep Over Stability

| Published: | Thursday, September 4, 2025 |

| Author: | Daniel Patterson |

The Age of Perpetual Upgrades

Another traditional and more permanent term for Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery is Feature Creep.

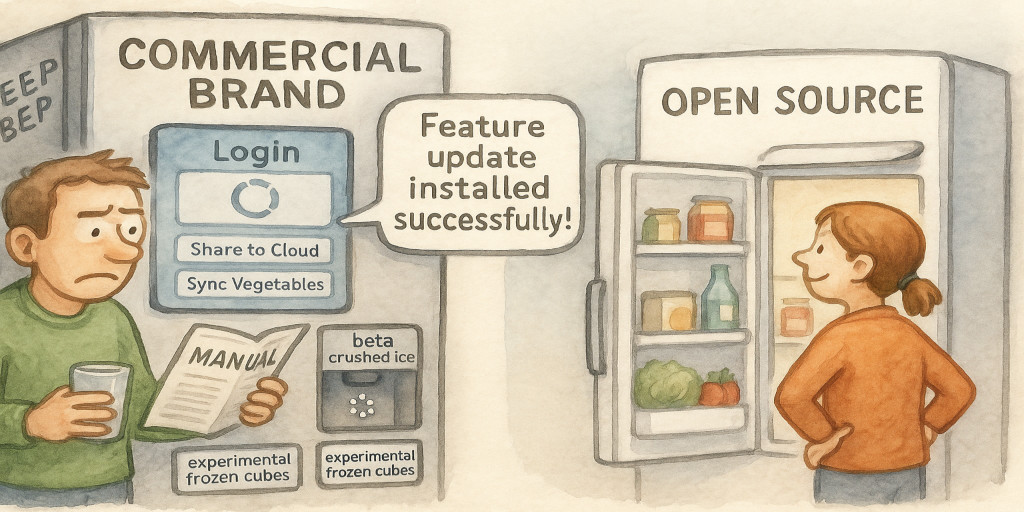

Modern technology companies have adopted an approach that forces their customers into a relentless cycle of updates and upgrades. Every week brings another round of patches, changes, and so-called improvements that demand time and attention from users who never asked for them. This process consumes not only the energy of billions of individuals, but also the collective man-hours of society on a staggering scale. Far from increasing stability, the vendors themselves are continually and directly introducing new bugs, undocumented behaviors, and unexplainable inconsistencies into systems that were more reliable in the past than they are today.

The global CrowdStrike outage of 2024 is a stark example of how extreme that culture of constant tinkering has become. A single faulty update cascaded through millions of Windows systems, crippling hospitals, airlines, banks, governments, and businesses overnight. The world came to a partial standstill not because of sabotage or hardware failure, but because of an unnecessary, poorly tested change forced into working systems.

In times past, manufactured products followed a different philosophy. A tool, appliance, or piece of equipment left the factory in a reliable state, and it remained reliable until it physically wore out or broke down. There were no weekly software patches for typewriters, no forced updates for toasters, no new version of a landline telephone unless a real and necessary improvement was needed, and in that case, only when human safety depended on it, due to the fact that it was such a logistical nightmare to execute a recall. When failure finally came in a product, it was attributed to wear, age, or consumer use, instead of any arbitrary or disruptive change imposed from the outside.

This ethic, of not making unnecessary changes, was once considered fundamental to engineering integrity. Improvements were reserved for the specific moments when they were truly needed, like carrying out a repair, addressing a genuine safety concern, or providing a meaningful enhancement. While adhering to this ethic, the typical engineer would repeatedly go back through the design objectives and test the system in any way they could imagine so they could be convinced that it was as near perfect as possible before letting it leave the premises. The constant churn of today's digital environment stands in stark contrast, siphoning attention away from users, degrading systems that once worked dependably, and replacing a culture of durability with one of instability.

The Hidden Consequences of Change

Every alteration to a system, however well-intentioned, carries risk. Once a working system is touched by a human, the chance of introducing error is effectively doubled from the state it was in before. With each subsequent change, those odds compound. This isn't alarmism, just awareness of the simple mathematics of human fallibility combined with the fragile interdependence of complex systems.

Modern software, in particular, is a web of interconnected functions, libraries, and subsystems. A small fix intended to correct a minor defect may inadvertently interact with another part of the system in unexpected ways, creating new problems exponentially worse than the one it set out to solve. Complexity multiplies risk. The more intricate the system, the more likely it is that a new change will ripple outward, breaking something unrelated but essential.

This principle has been tragically illustrated in high-stakes and everyday contexts alike. Following are some examples.

Aviation Systems. In the Boeing 737 MAX crisis of the 2010s, a new software layer, known as the MCAS system, was introduced to handle flight stability under specific conditions. What was framed as a minor adjustment had catastrophic side effects, interacting with faulty sensor data in ways that were not fully understood or tested. The result was two crashes and hundreds of lives lost.

Medical Devices. In the field of implanted medical equipment, there are well-documented cases where a firmware update meant to patch a rare bug instead introduced new instabilities. For pacemakers and insulin pumps, this has sometimes meant recalls, emergency interventions, or even life-threatening malfunctions.

Global Outage. In the CrowdStrike failure of 2024, that same faulty update which crashed millions of Windows machines showed just how fragile modern IT has become. One vendor's error cascaded through critical infrastructure worldwide, proving how a single, unnecessary update can ripple outward to paralyze industries and disrupt daily life for millions.

These examples underscore the larger truth that change is never free, or in the words of the great science fiction writer, Robert A. Heinlein, "There Ain't No Such Thing As A Free Lunch", otherwise known as TANSTAAFL.

Each modification is a dice roll against complexity, and most often, the people bearing all the risk in changes to a system are its users.

This is why stability once carried such value in engineering. An untouched, well-functioning system retains its reliability precisely because no new risks have been introduced. Any unnecessary modification is not neutral. It is a gamble that repeatedly puts users in the position of absorbing failures that never needed to exist in the first place.

Productivity Disruption: When Working Features Still Break the System

The problem of change goes beyond technical risk. Even when a new feature or redesign works as intended, it often undermines the human systems that have grown around the old one. Large organizations in particular depend on stable workflows, where entire departments may be structured around the predictable behavior of software. When vendors suddenly alter these behaviors, they don't just force users to click in new places, they can throw entire chains of responsibility and accountability into disarray.

Take the example of enterprise resource planning (ERP) software. Many companies maintain dedicated teams for tasks such as updating customer records. To ensure accuracy, these teams build peer-review processes where edits must be approved by designated reviewers outside the editors' reporting chain. If the software vendor abruptly changes the rules, requiring that edits must now be approved by the editors' own managers rather than the established reviewers, then the entire workflow collapses. The carefully balanced division of duties, the training of staff, and even the organizational chart may need to be rewritten overnight. Productivity suffers, not because of any technical malfunction, but because a vendor ignored the realities of its customers' working lives.

This same pattern recurs across industries. Here are only a few minor examples.

Customer Relationship Management (CRM). A sudden redesign of reporting dashboards can nullify years of standardized training and force sales teams to relearn where to find critical data. Deadlines slip, performance tracking is delayed, and managers scramble to rebuild lost reports.

Productivity Suites. Something as trivial as moving menu options in office software has historically created waves of disruption. The infamous transition from Microsoft Office's classic menus to the so-called Ribbon interface in the 2000s required companies worldwide to retrain entire workforces. This represented millions of human hours lost simply to restore previous productivity levels.

Collaboration Tools. When chat or project-management platforms change permission models or notification defaults, entire communication patterns can be destabilized. Teams accustomed to one mode of oversight might suddenly find critical messages silenced or rerouted, leading to confusion, duplication of effort, and missed deadlines.

In each of these cases, the feature might technically work because it doesn't crash the system, but it forces users to reorient themselves, retrain staff, and in some cases, reorganize departments just to get back on track. What was once a dependable tool becomes a moving target, steadily eroding confidence in the stability of the system.

The lesson here is simple and twofold. First, unnecessary change imposes hidden costs even when it doesn't introduce outright errors, and second, the harm is often just as much organizational as it is technical, multiplying the man-hours wasted and diverting attention from real work to constant, needless adaptation.

Open-Source Restraint and Engineering Ethics

Open-source software represents the opposite approach. Here, feature creep and unnecessary alterations are resisted through careful planning, deliberate collaboration, and respect for engineering ethics. Instead of racing to release flashy new features, open-source projects often err on the side of caution, prioritizing stability, security, and predictability. Change is introduced with purpose and with respect for the long-term reliability of the system.

This restraint is not a sign of stagnation, but rather a testament to correct engineering practice. The open-source community understands that software, like any engineered system, should be dependable and minimally demanding on its users. When updates occur, they tend to be transparent, well-documented, and respectful of user autonomy. They do not arrive as a barrage of distractions or disruptions; they are careful interventions meant to improve the system without degrading its foundation.

If a system is to remain reliable and to quietly serve its purpose without demanding constant user maintenance, it will most likely come from the open-source world. There, the ethic of restraint, deliberation, and responsibility continues to guide development. Meanwhile, commercial vendors remain trapped in the unstable cycle of endless features at the expense of stability.

werMake

werMake