Commercial Pain Points: Performance Degradation

| Published: | Saturday, September 6, 2025 |

| Author: | Daniel Patterson |

The Commercial Software Trap

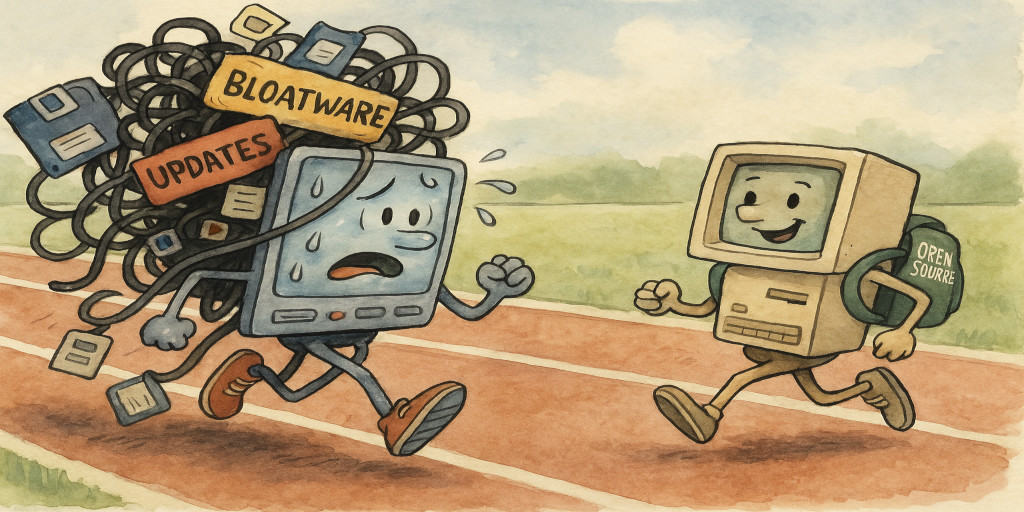

Commercial software and hardware almost inevitably become slower and less reliable as they age. This is not because of any inherent limitation of computing, but because of deliberate layering of features, dependencies, and constraints.

At the root of the problem lies a culture of stacking complexity. From compilers to sprawling interdependent libraries, developers continually introduce new abstractions that create intricate webs of dependencies into an ecosystem that has long been called a DLL hell. These libraries are proprietary, rarely ever documented in full, and they often introduce incompatibilities, leaving users, as well as potential maintainers from the public, with little or no recourse. They can't fix broken links or remove bloated components. Instead, they are forced to endure the slow creep of inefficiency.

The experience is familiar. The first time you install a newly published system, it feels dazzlingly fast. So fast, in fact, you might struggle to keep up with it. But over months and years, that speed dissipates into lag, stutter, and finally, waiting at every turn for the system to catch up. Commercial vendors often dismiss user complaints by claiming that customers have simply grown used to terrific performance, but side-by-side benchmarks consistently show the truth that the system really is slower, sometimes drastically so.

This slowing isn't only about raw speed. It's about reliability and correctness. With every layer of extra computation, subsystems grow prone to unexpected side effects. Minor functions that once worked consistently may begin to fail in subtle, illogical ways. Long chains of superfluous calculations multiply the risk of inaccurate outcomes.

The problem compounds with "bloatware", which refers to the pre-installed, largely unnecessary software that device distributors add to new machines. Even a brand-new system can boot sluggishly and feel like it's already years old. Vendors justify this expansion as progress, but the result is a constantly ballooning appetite for more powerful hardware.

All of this together establishes carefully choreographed dance throughout the technical industry.

- Software grows heavier, slower, and less reliable.

- Hardware manufacturers respond with faster, more resource intensive, and more expensive equipment.

- Software producers assure customers that performance problems will disappear with the next generation of machines.

- As soon as that hardware arrives, the cycle restarts, quickly eating up all of the new capacity.

The final outcome at every stage is waste. Whether wasted time, wasted resources, or wasted energy, the burden falls not on the producers but on the consumers and the environment.

The Open-Source Counterexample

Contrast this with much of the open-source ecosystem, where efficiency and longevity remain guiding principles. To be fair, open-source projects are not immune to creeping bloat. Entire dependency forests in NodeJS, or sprawling header files in C and C++ are often poorly managed and consume limitless resources when trying to manage an existing project dependent upon those libraries.

Yet the best actors in the open-source community set a very different example. Many of them treat every byte of memory and every cycle of CPU time as precious. Their projects demonstrate what is possible when resource stewardship is a cultural value.

Some open-source tools and applications are so lean they could still run on hardware from the 1980s. The Commodore 64, with its mere kilobytes of memory and clock speed thousands of times slower than today's phones, remains a benchmark that some developers keep in mind as a target for efficiency. Meanwhile, modern cell phones run operating systems that struggle to boot without gigabytes of RAM and they are considered efficient next to desktop PCs or big-brand office machinery.

Available examples are plentiful. Games like Doom have been ported to ancient hardware that commercial vendors abandoned long ago. Thousands of open-source projects extend the usable lifespan of computers by years, sometimes decades, allowing users to reclaim devices long consigned to closets or landfills. Instead of requiring ever-faster, ever-larger hardware, these systems reveal how modern features and functionality can thrive on modest resources, allowing for a drastic constriction on the consumption of resources without any actual inconvenience to the consumer.

And here lies one of the most overlooked advantages of the open-source ecosystem. Environmental kindness through efficiency. Every avoided hardware upgrade means less mining of rare earth metals, less manufacturing, less shipping, and ultimately less e-waste piled into landfills. If the open-source principals of resource stewardship were scaled to a drastically larger portion of the software landscape, the net demand on the environment could shrink by thousands of times compared to today's wasteful commercial cycle of forced obsolescence.

Commercial producers view growth as their only healthy trajectory, with new products, bigger platforms, more dependencies, and faster turnover of devices. In stark contrast, an open-source community doesn't require constant growth to remain vibrant. It can remain steady, productive, and sustainable for years, even decades, while serving its users effectively. Efficiency allows for stability, and stability allows for an environmental balance.

For users, the effect is liberating. They can continue using existing machines until the hardware itself physically fails. And they can breathe new life into forgotten equipment by repurposing, recycling, and reimagining what was once written off as obsolete. In the frugal words still followed by the majority of the agricultural community, Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.

Overall, while commercial producers externalize the cost of bloat onto consumers, open-source communities often prove the opposite. They show that with care, restraint, and discipline, performance can remain stable, or even improve, over time.

werMake

werMake