Commercial Pain Points: Aggressive Upselling

| Published: | Tuesday, September 9, 2025 |

| Author: | Daniel Patterson |

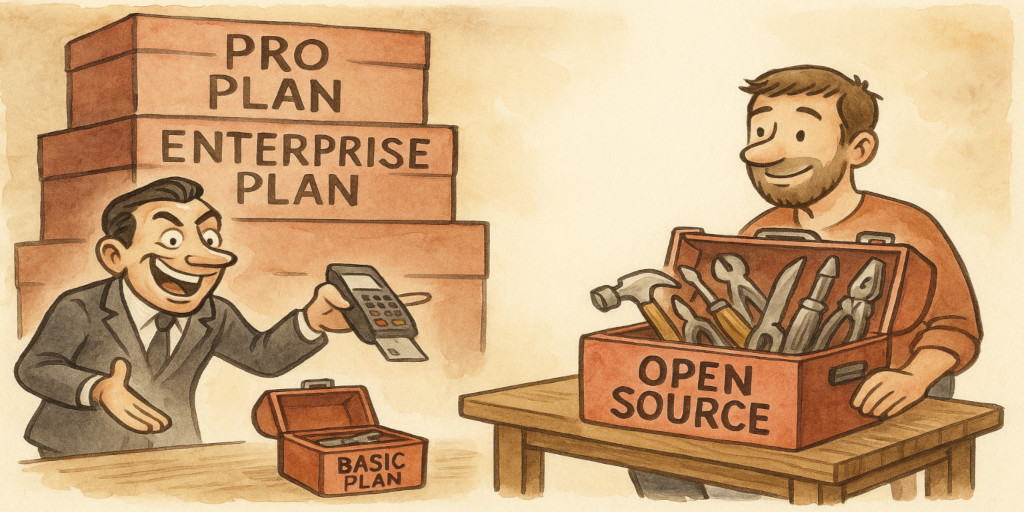

Commercial: Where Software Is Just a Sales Script

When engaging with commercial software vendors, consumers often find themselves immediately funneled into a carefully designed sales process. Simply visiting a company's website can result in a cascade of persistent marketing strategies, including pop-up windows asking if you want to "upgrade now", banners warning that your productivity could be at risk without the premium package, or chatbots appearing in the corner to push you toward a trial or a perennial limited-time offer. What once might have been a casual inquiry into product capabilities has eventually become a minefield of constant distractions and sales nudges. For those who go a step further and speak to a representative, either over the phone or in person, the pattern continues with polished scripts, carefully timed pauses, and relentless attempts to upsell at every tier. Even after leaving the website, many customers report being followed across the internet with targeted ads, each one more insistent than the last, reminding them of what they might have left behind in their shopping cart.

Modern advertising has evolved far beyond simply announcing a product's existence. What we now encounter is not just active marketing, where companies deliberately place messages in front of us, but an aggressive escalation of that practice. Marketing today is designed to invade the mental space of potential customers, attempting to capture attention through urgency, fear of missing out, or sheer repetition. Each click online seems to deepen the net of retargeted ads, emails, and notifications. The strategy is not simply to make people aware of a product but to keep it in their face until acquiescence feels like the only way to regain peace of mind. Customers rarely have the chance to evaluate the product on its merits before being bombarded with layers of psychological persuasion.

This intensity of promotion is not incidental. It is deeply tied to how commercial software is structured. Rarely do these companies sell a single, stable product at one transparent price. Instead, they create complex, tiered ecosystems that include all of the generally accepted formats like basic, pro, and enterprise, where the lowest rung often feels intentionally restricted. Starter or economy levels sometimes offer just enough utility to be technically functional, but not enough to deliver genuine productivity. Far more than a comfortable number of essential features are placed behind paywalls, always nudging users toward higher-priced plans whether or not those features are truly necessary. The customer is never any longer asked what they need, but rather, how much they would be willing to sacrifice to get something useful, and large commercial organizations are always more than happy to accept receiving as significant a piece of the customer's own income as possible.

At its core, the business model of large commercial software vendors revolves around the sales funnel. Every element of the customer's journey is engineered to lead to the next level of purchase. Product trials are often limited not by time but by access to crucial functionality, ensuring that frustration sets in quickly. Customer service representatives are incentivized not to resolve issues at the base tier, but to encourage upgrading as being the only legitimate solution. Even the vernacular they use, like unlock, premium, and full access, just to name a few, implies that customers at lower levels are being deliberately held back. The funnel, rather than the product's effectiveness, becomes the true centerpiece of the vendor's strategy, and productivity can not be guaranteed at any stage, because it is conditional on continued spending.

Open-Source: Just Tools, Not Traps

In drastic contrast, the open-source community tends to embrace a very different approach. Open-source projects rarely rely on the mechanics of a sales funnel, because they are not directly profit-driven in the same sense as commercial vendors. Instead of orchestrating constant reminders, pop-ups, and targeted ads, open-source creators usually adopt a passive marketing strategy. Their efforts are focused on making the software discoverable for those who are already looking for it, meanwhile maintaining public repositories, writing documentation, and engaging in community forums. The implicit understanding is that a user's attention is a valuable, limited resource, and that constantly interrupting it does not properly serve either the project or the individual.

This passivity is not a sign of weakness but of respect. Many open-source developers are also professionals, students, or researchers themselves. They know firsthand how disruptive it can be to have one's focus hijacked by relentless marketing tactics. As a result, the community tends to place a premium on letting users approach at their own pace. A prospective user may hear about a project through word of mouth, a conference presentation, or a simple search query, for example, but they will rarely be chased across the Internet afterward. Instead, the main emphasis is on building trust. The software is offered freely, its source code is transparent, and the value proposition is clear from the start.

Another significant distinction lies in the way features are presented. In open-source ecosystems, the base tier is not artificially limited. That is the complete product, as it exists. If functionality is absent, it is because the community has not yet developed it, or customized it, or configured it in that way, not because someone has intentionally locked it behind a paywall. Contributions from users often help expand the project over time, and extensions or plugins tend to be offered openly by other members of the community. The result is that users can evaluate and adopt the software based on genuine capability, not because they have been maneuvered into an upgrade.

Additionally, open-source projects often shift the focus from pure consumption to interactive participation. Instead of asking what they could sell you next, the community asks what we can build together. This creates an entirely different atmosphere of collaboration rather than transaction. Users are not treated as customers to be maximized for revenue, but as a community of contributors who can shape the future of the software. This sense of agency stands in sharp opposition to the helplessness many feel when dealing with commercial vendors, where choices are artificially constrained by business goals rather than technical possibility.

The practical benefit of this difference is significant. By sidestepping the noise of aggressive upselling, open-source users are free to focus on what truly matters, which is whether the software actually meets their needs, and if not, what can possibly be done about that. Their attention is spent on learning, customizing, and applying the tool, not on dodging constant reminders of what they have not yet purchased. In a world where attention is increasingly scarce, this restraint by the open-source community can be viewed not just as a kindness, but as a competitive advantage.

Conclusion

Aggressive upselling has become an unavoidable reality in the world of commercial vendors. The constant intrusions, limited starter tiers, and relentless focus on the sales funnel all work together to prioritize profit over productivity. For customers, this means navigating a maze of distractions before reaching any semblance of value.

Open-source producers, however, embody a different principal. Their passive approach to marketing, respect for user attention, and emphasis on complete, transparent offerings present a powerful alternative. Rather than treating individuals as leads to be converted, they treat them as collaborators and peers. In doing so, they remind us that software does not have to be a never-ending upsell. Instead, it can be a tool for empowerment, discovery, and shared progress.

werMake

werMake